Becoming a virus

Mateo Martínez Abarca/ translated by Alicia Barrón López

Philosopher, writer, and political analyst. Member of the seminar «Modernity: versions and dimensions» of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and of the CLACSO working group «Anticapitalisms and emerging sociabilities».

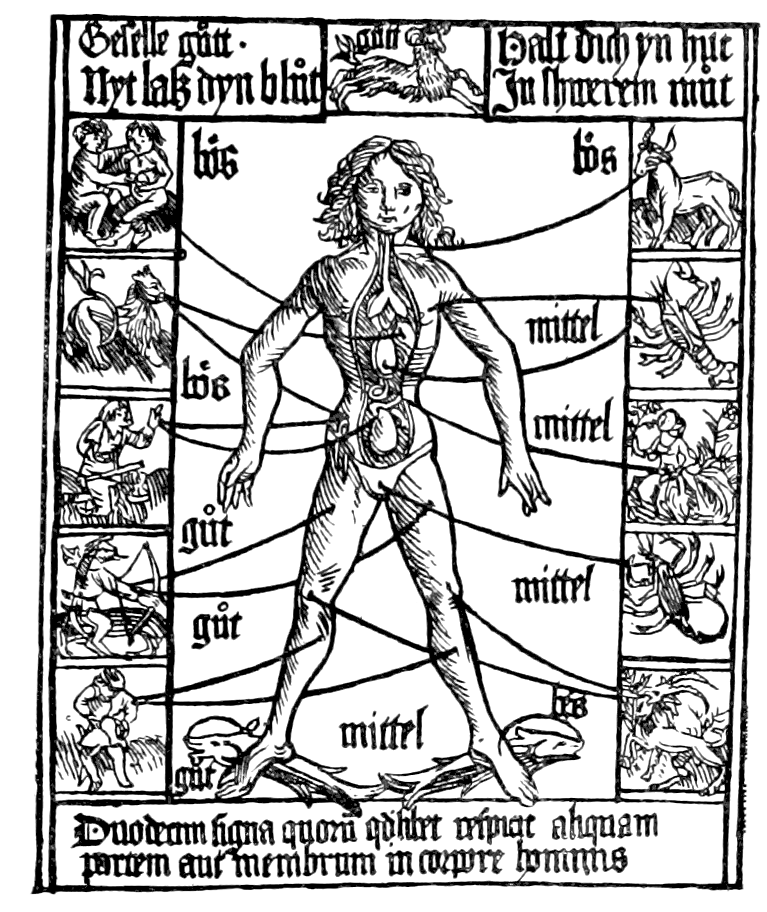

A few years ago I had the opportunity to meet American philosopher Susan Buck-Morss personally and to participate in a seminar that she taught for five days at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. In one of the several sessions dedicated to discussing her work, she referred to an investigation that she was developing at that time about the meaning of History, based on a reading of various ancient texts articulated around the Benjaminite concept of dialectical image. Among the things that amazed me the most about her approach was an interpretation of the Book of Revelation by Juan de Patmos, represented in an iconographic manner in the beatus of Saint Severus, written in the north of the Pyrenees in the 11th century. The Beati are illuminated codices typical of the central and northern areas of the Iberian Peninsula which are richly illustrated and in which different cultural influences intermingle, particularly Visigothic, Romanesque and finally Mozarabic. These texts contain several biblical elements, yet commentaries on the Book of Revelation are the main focus.

Based on the analysis of the beatus, Susan sought to prove a highly suggestive hypothesis, by which the text of John of Patmos could actually thoroughly be read as a genuine history text, however narrated in a tone of prophetic inspiration. Several of the events symbolically represented in the Book of Revelation, would actually correspond to events during the life of John which would have been written around the end of the 1st century AD. In particular, he referred to the persecution of Christians by emperor Nero; the destruction of the second temple of Jerusalem by Titus during the rebellion of the Jewish people, somehow prophesied in the Gospels; the eruption of Vesuvius in 79, whose ash cloud plunged almost the entire Mediterranean into darkness for some time, and the deep internal political conflicts within the Roman Empire, which ended with the fall of the Julia family dynasty , thus opening a long period of instability.

“Then the seven angels who had the seven trumpets prepared to blow them. The first one blew the trumpet, and hail and fire mixed with blood came, and they were thrown to the ground; and a third of the earth was burned, a third of the trees were burned, and all the green grass was burned. (Revelation, 8: 6-7) Beatus of Saint Severe, circa, 1050-1070. National Library of France.

“Then the seven angels who had the seven trumpets prepared to blow them. The first one blew the trumpet, and hail and fire mixed with blood came, and they were thrown to the ground; and a third of the earth was burned, a third of the trees were burned, and all the green grass was burned. (Revelation, 8: 6-7) Beatus of Saint Severe, circa, 1050-1070. National Library of France.

All this commotion is symbolically reflected in the Book of Revelation, leaving its mark on the eschatology of Western Christian Jewish culture to this day. Following Benjamin, ancient myths can only have meaning in terms of their actualization, when they become facts in the present, enclosing clues for decoding what is absolutely new in modernity. In this sense, for Susan Buck-Morss images and symbols, such as those represented in the text by Juan de Patmos, cease to be mythical and become genuinely historical «insofar as they refer to real historical possibilities even the most common everyday secular phenomena are therefore capable of carrying political significance of political significance” (Buck-Moss, 2001: 275). Based on this, as events of the present inevitably take on an apocalyptic tone, it is worth venturing into a decoding of their meaning. How will a historian read this time of radical crisis in about two thousand years? Of course, if there are any human beings left by then.

As Fernand Braudel points out in Civilización Material y Capitalismo, epidemics and endemics have been recurrent throughout the history of humanity and have continued to expand on a global scale especially since the modern era, a period in which nature and the countryside regress in contrast with the growth of cities and exchanges (of goods, labor force, culture, and pathogens). The expansion of the Mongols revived the Silk Road and brought the Black Plague with it; smallpox brought to America by European conquistadors wiped out much of the indigenous population; and in return, a mutation of syphilis from the New World reached Europe, even before corn, and then spread to China. These epidemics have been worsened as a consequence of the discrimination and precariousness in people’s lives. For example, in some parts of seventeenth-century Europe, since the disease was announced «the rich have rushed to their country houses, fleeing in haste, nobody thinks about anybody but themselves»; and as for the poor, ”says Braudel,“ they were left alone, prisoners of the contaminated city where the State fed them, isolated them, blocked them, and watched over them ”(Braudel, 1979: 59). Jean Paul Sartre would say, a long time later, that the plague only acts as an exaggeration of class relations, it hurts the poor, it forgives the rich.

It has been a small virus that has brought us, once again, to this moment of urgency and uncertainty, in which so many things are anticipated, as if we were at a threshold in the midst of the ruins of history. Fragile as they are, our bodies suffer. It is not only the disease, but the nostalgia of our rights, blown up for so long by some of the horsemen of neoliberalism. It is also confinement, the control and militarization of life, which after all are among the most elaborate repressive fantasies of capitalism, which today are mixed with the rise of teleconsumption: everybody at home, but still disciplined buyers. And when this is not possible, as in most cases, hunger comes, a phenomenon which is beginning to emerge especially in our southern countries, in which the majority of the precarious and impoverished population survive day by day with the minimum to eat and for whom it is not an option to remain in quarantine. As it happens with the consequences of climate change, capitalist realism assumes that technique or the market will also solve the problem, while capital continues to multiply beyond measure and the crisis is nothing more than a kind of temporary simulation. It will be a matter of a few days or weeks for this realism to take control, the dead will be placed in the balance along with the economic losses and the gears of exploitation will begin to move again. Because capitalist accumulation cannot be interrupted indefinitely.

In fact, the epidemic is fulfilling a double function under the dictatorial regime of capital. On the one hand, it is the perfect motivation to accelerate a set of measures that would make it possible to not only save the global processes of capital valuation and capital accumulation, but also to optimize them towards the future, just as it would happen in a war situation. Layoffs, salary cuts, financial bailouts or austerity measures are beginning to be implemented in some countries, thanks to a parodic return of speeches in favor of the Welfare State. The apocalypse has pushed some unrepentant neoliberals to abjure their religion, to suddenly become salvific Keynesians. On the other hand, this epidemic fulfills a similar function to that of a general strike by workers: to paralyze the apparatus. Of course, it is not a general strike built on popular organization and solidarity, but merely a consequence in which global exchange relations, such as those described by Braudel, have produced it «naturally». What is preventing us from resignifying what is happening and turning paralysis into a strategy of struggle? In fact, it could be the first major global general strike in history.

For us, who are on the left bank of the river, it is not really necessary to emphasize that the elements that make up this crisis are genetically inscribed in the series of unsolvable contradictions that cross capitalist modernity from beginning to end. Hence, much of our efforts focus on the constant prefiguration of utopia and the maintenance of hope in what is not-yet, as we face the recurring imminence of collapse. It is a difficult task, because every day news reports provide us with news of the advance of the Four Horsemen around the world and they do so in comfortable doses that only reaffirm a certain collective indifference: war here and there, natural devastation and climate change, suffering of hundreds of thousands of migrants between the global south and north, deep social conflicts and even locust plagues. And to top it all off, now the plague. However, those who are best decoding and exploiting these very powerful images of the end of the world are right on the other side, inhabiting the new fascisms that appear as an infection everywhere. It is not difficult to understand why, if we put ourselves in the place of the vast majority of the population and try to assume their gaze that ranges from disappointment to anger.

Satan and the plague of locusts (detail). Beatus of Saint Severe, circa, 1050-1070. National Library of France.

Satan and the plague of locusts (detail). Beatus of Saint Severe, circa, 1050-1070. National Library of France.

However, the rate of formulation of our alternatives to barbarism seems to be less than the speed with which it is unleashed. Moreover, although struggles and rebellions erupt everywhere, like lightning bolts on the horizon (in Ecuador, Chile, France, Iran and so many other places), we continue to wonder secretly or openly if we really have an opportunity to change this trajectory that takes us closer and closer to the abyss. Are we too pessimistic? Reality is not Hollywood: it takes more than hope to transform it and we have taken for granted that reflection by Fredric Jameson, so repeated these days, that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. That is why we are better trained to recognize the ability of capitalism to adapt to crises and the ways in which it finds opportunities to consolidate, than to acknowledge the moments of systemic breakdown through which revolution can sneak in. Thus, we involuntarily engage in the reproduction of a logic in which we perpetually witness the end of the world, elevating it even to the category of aesthetic enjoyment, paraphrasing Benjamin himself.

Perhaps the point of all of this is to turn this authoritarian edict around, to break the learned logic and begin to represent the imminence of the end of capitalism before that of the end of the world itself. Both the Revelation of Saint John and the commentaries that appear in the various Beatus had the political function of influencing and shedding light on the present. It is a matter of urgency to reinterpret the power of the current apocalyptic images, hoist the sails against the wind of History, awaken from the dream and begin to materialize another present. It is so because this is also a fight over the field of forces / meanings that are not given in absolute terms, and consequently our current task would be to leave behind our sleepy leftist melancholy and not to dedicate all our efforts to the non-place of utopia or the not-yet of hope, but to the yes-here as a radical affirmation -at this very moment- of the power of life. Perhaps that way, the overwhelming and deadly dynamics of the virus itself (similar to that of capital) can be interpreted differently and teach us to clarify the vulnerabilities not only of our bodies, but of the system itself. There is no time for waiting or fear, we must find new weapons – Gilles Deleuze said. And this epidemic is a miniaturized war machine that is already being used against the population, but in which we can also attempt to take a détournement the situationist way so that we can redirect it against the deterritorialized body of capital, that subject that has taken our place as protagonists of our own story.

Is a true revolution impossible today? Guattari asks himself in Molecular Revolution. The answer is no. What it would require would be the deployment and expansion of countless emancipatory practices, each of them linked to each other, weaving solidarity, rapidly invading the genetic code of forms of oppression (capitalist, patriarchal, colonial), it would require transforming this confinement into a critical mass, into a viral general strike, so it could then hatch abruptly like an Alien from within Moloch, that god that we sacrifice ourselves to daily. To be able to do this, it might be necessary to surrender to the reverie of prophetic enlightenment, to come together to become viruses and reveal that this is really the apocalyptic moment of the final fight.

Bibliography:

Buck-Morss, Susan. (2001). Dialéctica de la mirada. La balsa de la Medusa. Madrid.

Braudel, Fernand. (1979) Civilización material y capitalismo. Alianza Editorial, Madrid.

Guattari, Felix. (2017) La revolución molecular. Errata Naturae, Madrid.