The silenced anatomy of COVID-19

Maria Paula Meneses | Traslated by Alicia Barrón López

Researcher Coordinator

Vice-President of the CES Scientific Council

Centro de Estudos Sociais/Center for Social Studies (CES) – University of Coimbra

COVID-19 in numbers

The new coronavirus has officially been declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO); up to now, it has infected ten times more people than SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, caused by a virus related to the new coronavirus). COVID-19 is a highly contagious and potentially deadly respiratory syndrome, as it has been reported by media around the world. Until now (March 18th), there are over 8,000 deaths and more than 200,000 cases of infection have been identified. China remains the country with the highest number of deaths, despite the fact that the current focus of spread is mainly Western Europe.

As I write this text, I continue to receive information about the spread of COVID-19 throughout the African continent. Even if a couple of weeks ago several newspapers were wondering why there were such few cases of infections caused by the new coronavirus, reality today is quite different: in Africa more than 500 cases of COVID-19 have been diagnosed in more than half of the countries of the continent, where there have already been several deaths. Among the most affected countries are Egypt, Algeria, South Africa, Senegal and Morocco.

The chain of transmission of most of the more than 60 cases of coronavirus identified in South Africa, Eswatini and Tanzania, neighboring countries of Mozambique, began mainly in the European context: Italy, Spain, Austria, United Kingdom, Germany, The Netherlands, France and Switzerland; other sources of contagion are Brazil, the United States and Iran (although local transmission chains have already been identified).

COVID-19 in Africa: the origins of pollution chains

There are several hypotheses that may explain the delay in the arrival of COVID-19 in the African continent. First, climate conditions. Apparently, coronavirus does not like heat. This factor, associated with the fact that most of the population of the continent are young people, helps explain the still low rate of coronavirus infection, although there are doubts about the veracity of detection rates. Even though China, where the pandemic started, is Africa’s main trading partner… how can the low rates of contagion from Asia be explained? Could the quarantines the citizens of China have been subjected to be one of the reasons that have been able to limit the spread of the virus to African countries? This data is surprising, since the African continent is usually perceived by the global North as a space of problems. The term ‘shit countries’ (shitholes), that is, African countries, to use the designation of the president of the United States, shows a racialized hierarchical view of the value of African countries and their inhabitants. However, an analysis of the anatomy of this pandemic offers us a different image.

The number of Europeans diagnosed with coronavirus in Africa has led to a debate about the continent’s security. Recently, a Senegalese newspaper even joked that France planned to ‘coronate‘ its former colony, after two French citizens, who had just returned to Senegal, were diagnosed with COVID-19. In the case of Nigeria, the first person with a positive diagnosis was an Italian citizen who returned to work after spending a vacation in his country. Currently, Italy, Spain and France are among the countries with the highest number of infected people.

The difficulties Africans face when entering Europe also help explain the late arrival of the virus via Europe. However, as initial preventive measures against coronavirus transmission focused on reducing (or even canceling) travel, especially to and from China, the current situation suggests that links between Africa and Europe are a focal point of vulnerability for the African continent.

Among the drastic measures that are being taken in several African countries to contain the pandemic, together with the implementation of national systems to monitor infected people and all those with whom they have been in contact, comes the draconian limitation of traveling both abroad and internally; the closing of borders; the ban on meetings; the cancellation of public celebrations; the immediate closure of schools and universities; the intensification of hygiene control and massive information campaigns on the risks of COVID-19, trying to dispel myths, etc. (https://www.africanews.com/2020/03/17/coronavirus-south-africa-confirms- first-case /) To sum up, the pandemic shows us that the enemy, the virus, leaps distances and crosses borders, especially now, since passenger air traffic to Africa has almost doubled in the last decade.

Africa is part of the global economy, and it is linked to the world in many ways. Air travel and commercial networks spread viruses quickly and quietly. Implementing travel bans means jeopardizing business opportunities, investment, and tourism opportunities, a major source of income for the African continent. But traveling is particularly dangerous when, as in the case of the coronavirus, there are still no vaccines.

With this pandemic still in its initial stages, it is difficult to anticipate the true impact of COVID-19 in Africa. What kind of scenario awaits us?

Several actions are underway. National governments, with the support of WHO and other international agencies, have strengthened both the capacity of African countries to detect the virus and the training of health professionals to treat infected people.

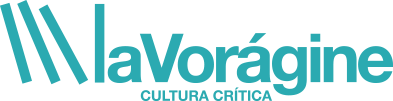

The anatomy of public health

The present pandemic exposes the anatomy of public health and the social justice dilemmas developing countries are facing. COVID-19 poses numerous problems for African governments and their health authorities. It is important to contain the spread of this new virus in a continent that has about 1.3 billion people (mostly young; 60% of the African population is under 25 years old). With the spread of the disease across the continent, the impact of this pandemic in countries with fragile health systems will be a large-scale disaster. In addition, several contextual realities must be taken into account.

The intense phenomenon of urbanization in Africa has transformed cities into densely populated neighborhoods with often little infrastructure. Governments and organizations have been asking people to maintain the necessary social distance to help reduce the rate of COVID-19 infection, but how do you apply this distance when, for example, informal markets and door-to-door commerce are one of the main sources of family income? How to avoid mass transportation in contexts where public transportation services are insufficient in themselves?

One of the recommendations from WHO and the Mozambique Ministry of Health is important: wash your hands regularly, since soap and water are excellent for fighting viruses. However, many of the houses in popular neighborhoods still do not have running water. Only 49% of the Mozambican population has access to drinking water, with urban areas being the most favored, with 80% access. Drought and irregular rainfall worsen this situation in the southern region of the continent. This leads to restrictions in the supply of this precious liquid, in Mozambique this happens particularly in the cities of Maputo, Matola and Boane (in total, these cities have more than 4 million inhabitants) or, in South Africa, in Johannesburg and other cities. In South Africa, difficulties for access to water are similar: only 46% of people have access to drinking water at home (89% of South Africans have access to drinking water).

The arrival of COVID-19 in Mozambique, as well as in other African contexts, is facilitated by the highly unequal context inherited from colonial-capitalist relationships (Mozambique gained independence in 1975). The destruction of native habitats, large-scale commercial agriculture, rapid urbanization, and the weakening of social safety nets create conditions for the existence of densely populated neighborhoods, with dramatic consequences in the face of epidemics. The inability of the Mozambique State to meet the urgent and basic needs of its citizens almost half a century after independence puts us all at risk. Let’s not forget, for example, that the presence of several million HIV-positive Mozambicans causes a significant part of the population to have a weak immune system, facilitating the rapid spread of COVID-19. The situation is urgent and shows the anatomy of our vulnerabilities. Studying them is understanding the structure of society, political priorities, reminding us that, despite the inequalities that characterize our countries, our lives and our future are intertwined and are part of the world.

Learning from the global South

Europe is failing to suppress the pandemic. It is important to learn from other experiences. One of the lessons coming from Asia (China, South Korea) has to do with the rapid detection of infected patients and, above all, with free testing. In China, treatment is also free. A pandemic is not suppressed by private health systems, which accentuate social inequalities. If the new drugs are only available to those who can buy them and become merchandise for profit, the health system will create more social imbalances. The presence of the State, through programs that support and promote public health, enables all citizens, regardless of income, to go to health centers for support. These are the lessons that can be learned from the various epidemics that have impacted the African continent in the last decades (for example, cholera or Ebola).

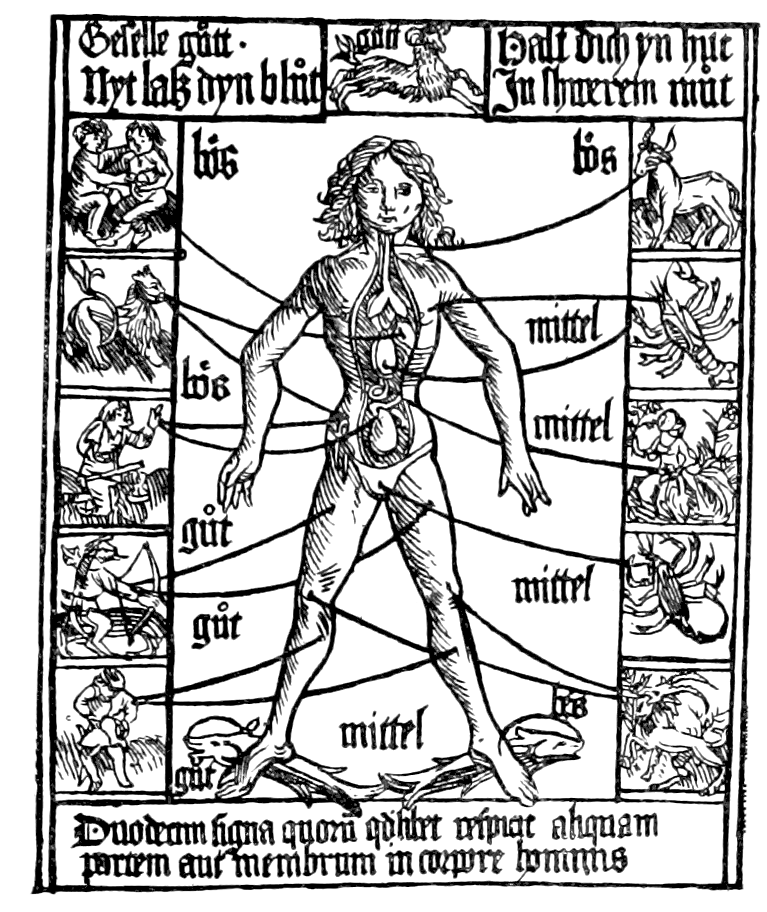

In fact, the consequences of recent epidemics and pandemics (for example, SARS, H1N1 or Ebola, the latter with a mortality rate of 50%) that impacted the continent highlighted the importance of the public health network, including disease surveillance systems and laboratory networks, as well as staff training (for example, surveillance training, epidemic response, and diagnostic testing).

As several African doctors and epidemiologists have been reaffirming, it is important to use the Ebola lessons to eliminate the coronavirus pandemic. This means following all prevention methods: avoiding direct social contact; handwashing; avoiding public places. Another measure taken that helped save lives was the zoning of hospital spaces, with isolated Ebola patients in high-risk areas. Prevention and control, with the support of communities, seem to be the key actions for the successful experience of overcoming a virus as contagious and lethal as Ebola. Another important factor is the solidarity and collaboration of doctors and nurses. These teams (including natives from South Africa, Cuba, China, etc.) jointly contributed, with their knowledge, experience and dedication, to controlling the pandemic. But the human element should not be neglected. Building trust in the community is critical to the success of any public health program. This includes challenging false news and rumors. It means working horizontally with people and convincing local leaders to collaborate in the dissemination of vital information. Building bonds of trust takes time, so if we want to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, it is essential to work immediately. Public health is a relationship of trust where patients are human beings, with families who care about them. Moreover, families need to know what is happening to their patients, in a transparent, friendly and open way. It is a human public health, a public health based on proximity.

Beyond the impact of colonial capitalist legacy

It is important to try to understand these epidemics, in each case, based on a careful analysis of the relationship between nature and society. Industrial agriculture is invading the habitats of animals that are natural hosts of infectious agents, such as bats, civets, and pangolins, for example. Also, the consolidation of intensive agriculture has led many peasants to lose access to land, pushing them to the edge of the cities.

Many of the current proposals for political change related to health seek to apply in many African countries a liberalized health system (that is, with first and second quality medicine). This is happening in Mozambique, where there are expensive private health services and underfunded public hospitals. This measure is not adequate to confront the risks of the epidemics that continue to appear. Viruses do not conform to social asymmetries. If we don’t take care of each other, none of us will be taken care of. When pandemics hit, such as Ebola’s, measles in 2019, or now COVID-19, we will all potentially face the same risk, even those with access to private medical care.

The coronavirus pandemic may be a historic opportunity for African governments (among others) to enact reforms to rethink economic options, address urgent environmental threats, and ensure that health and well-being are treated as public goods rather than opportunities to get economic profit. We need transparency, a democratic use of knowledge about diseases, open communication and dialogue with people and not about people.

Facing an epidemic requires collective effort and work, it requires timely global action that protects all people. A careful analysis of each situation and the dissemination of news and successful experiences are acts of solidarity, of co-construction of knowledge about the cycle of any epidemic. As the media reveals, this pandemic has disrupted economies, it promotes the stigmatization of individuals, groups, behaviors, and lifestyles. We want to express our immense solidarity with the Italian and Chinese population, who have been the target of racism and xenophobia.

Viruses move quickly, they cross borders undetected. Coronavirus is a global crisis that poses a challenge to the scale of our humanity. Facing this pandemic requires us to come together, learning from one another in solidarity. If there is one thing we learn from Ebola, it is that it is important to fight for universal public health care to ensure that the power of contemporary medical knowledge is used for the benefit of everyone, and not just some. If there is something we can learn from Europeans and Asians now, it is that we cannot continue presenting an image of African people as if they were bodies deprived of life and action. This pandemic highlights our radical need for sensitivity to guarantee the right to feel pain, in private. Thus, we can continue to identify what is wrong in our colonial-capitalist times and what alternatives must be promoted to sow a future for all. It is not the virus that is at stake, it is us, humanity.

These lessons from the South are here for us to use, let us not waste the wisdom from this experience.